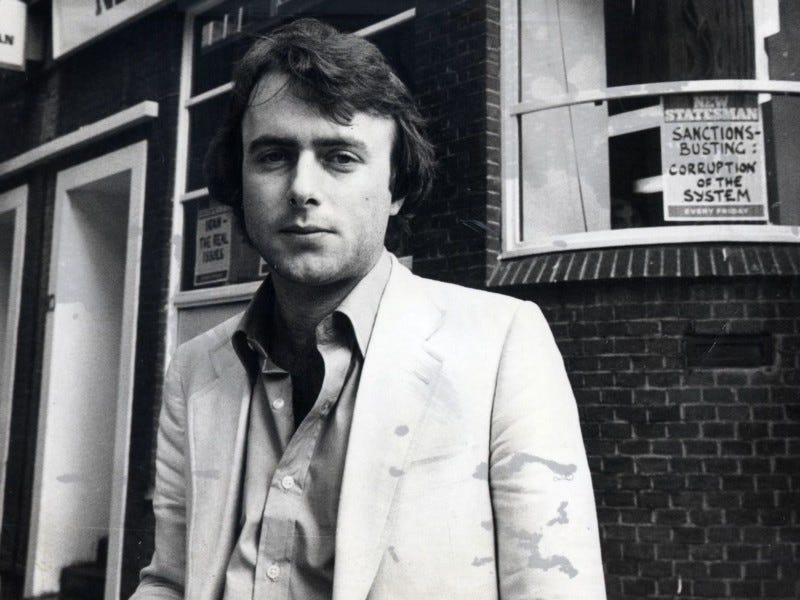

Hitchens' Fall From Grace

A look into his descent into neoconservatism.

It is not exceptionally common to see a liberal civil rights activist turn into a Reaganite neoconservative within the span of just a few years. But the Oscar-winning actor and WWII veteran Charlton Heston did just that, and by the end of the century, he had exhausted the list of the most conspicuously diabolical political positions a conscious being could hold. But perhaps the thing that most stands out about the likes of Heston was their support for the 1991 Gulf War—which was undertaken for mostly energy interests—under the pretense of protecting Kuwait’s sovereignty.

Who better to propagandize the war's purported benevolent motives than a reactionary like Charlton Heston? And so when he faced Christopher Hitchens in an infamous 1991 CNN segment to debate the intervention in Kuwait, there was hardly anyone as adept at cutting through imperial propaganda with comparable wit and brilliance as the then 42-year-old left-wing journalist. When Heston failed to meet his elementary challenge of naming four countries that border Iraq, Hitchens did not just expose him for the ignorant he was (“If you’re in favor of bombing a country you might pay it the compliment of knowing where it is,” he remarked.) He also exposed the dangers of an amoral foreign policy governed by corporate interests with the aim of imperial hegemony. Indeed, it is also not exceptionally common that an anti-war socialist like Christopher Hitchens would later end up schilling for the same imperialist agenda that he once so fearlessly dismantled.

Born in 1949 in Portsmouth, England to two WWII veterans, Hitchens was exposed in his teen years to works by leftist intellectuals like Richard Henry Tawney and George Orwell which influenced his subsequent anti-capitalist views. He later graduated from Oxford in 1970.

Hitchens’ political awakening occurred during the 1960s anti-war movement opposing the Vietnam War. In 1965, he was expelled from the student wing of the Labour Party for criticizing Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s “contemptible” support for the war. The horrendous murder program that characterized Western foreign policy in Vietnam created in him a skepticism of state power and foreign intervention. The chemical warfare waged against the population during the war still affects Vietnamese children to this day. When he later visited the country, Hitchens' chilling description of a Vietnamese child paints a sordid picture:

The little creature was not lying torpid and still. It was jerking and writhing in blinded, crippled, permanent epilepsy, tethered by one stump to the bedpost and given no release from endless, pointless, twitching misery. What nature indulges in such sport? What creator designs it?

Hitchens described himself as a “radical” and continued to identify as a democratic socialist for most of his life. In 1981, he became an editor for The Nation, one of the few prominent left magazines in the U.S. Certainly, his popular 1986 debate with the “objectivists” remains relevant to this day for understanding the right-libertarian fantasy world. “I always thought it quaint, and rather touching that there is in America a movement that thinks people are not yet selfish enough…. It’s somewhat refreshing to meet people who manage to get through their day actually believing that.”

With some semblance of his anti-war past still present, his The Trial of Henry Kissinger (2001) remains arguably the most incisive and scathing indictment of not just Henry Kissinger, but also of the international legal bodies’ consistent failure to hold war criminals like him accountable:

The burden therefore rests with the American legal community and with the American human-rights lobbies and non-governmental organizations. They can either persist in averting their gaze from the egregious impunity enjoyed by a notorious war criminal and lawbreaker [Kissinger], or they can become seized by the exalted standards to which they continually hold everyone else. The current state of suspended animation, however, cannot last. If the courts and lawyers of this country will not do their duty, we shall watch as the victims and survivors of this man pursue justice and vindication in their own dignified and painstaking way, and at their own expense, and we shall be put to shame.

And yet, Hitchens had been a complicated figure. Just two years before The Trial of Henry Kissinger, his support for the NATO-led bombing of Yugoslavia portended the subsequent rupture in his relationship with the left, an episode about which he later remarked:

That's when I began to first find myself on the same side as the neocons. I was signing petitions in favour of action in Bosnia, and I would look down the list of names and I kept finding, there's Richard Perle. There's Paul Wolfowitz. That seemed interesting to me. These people were saying that we had to act.

It certainly wouldn’t be the last time he found himself “on the same side as the neocons.”

Hitchens' shift to the right crystallized after the 9/11 attacks when he threw his weight behind the “war on terror” launched by the Bush Administration.

As Bush declared in his 2003 speech, the justification for invading Iraq centered on, among others, two claims; that Iraq allegedly possessed weapons of mass destruction, and that it “aided, trained and harbored” al Qaeda.

Despite both of these claims being repeatedly outed as pure fabrications, it will remain a mystery as to why a self-described skeptic like Hitchens, in a stupendous display of naiveté, would obsequiously swallow up every single lie conjured up by the State Department.

Moral dissonance had become somewhat of a hallmark. Hitchens, on the one hand, criticized the conservative fantasy of American exceptionalism. But on the other, to justify the Empire’s worst crimes, he regressed to a breed of infantile reasoning whose jingoistic folly may find (un)intellectual equivalence in no one other than Sam Harris. For instance, take Hitchens’ attempt to rebut Noam Chomsky’s comparison (not equivalence) of the Al-Shifa bombings to 9/11. His argument can be fairly reduced to one sentence: “Our intentions were good.” Almost 14 years later in 2015, Harris would make the exact same argument about “good intentions” in an email exchange with Chomsky. Both Hitchens and Harris justified endless imperialism under the pretense of good motives. Although, unlike Harris, Hitchens at least had the truistic sophistication of opposing torture (albeit after having to experience it himself).

His support for the war directly led to his split with his erstwhile leftist allies. He resigned from The Nation in 2002.

He had developed an almost sociopathic infatuation with muder. The Fallujah massacre of 2004, in which thousands of civilians were indiscriminately gunned down, was not deadly enough for him as the death toll was “not nearly high enough.” It is almost as if he had abandoned any pretense of “liberating” the Iraqi people and was entirely—one might even say voluptuously—obsessed with killing for killing’s sake:

We can’t live on the same planet as them and I’m glad because I don’t want to. I don’t want to breathe the same air as these psychopaths and murders [sic] and rapists and torturers and child abusers. It’s them or me. I’m very happy about this because I know it will be them. It’s a duty and a responsibility to defeat them. But it’s also a pleasure. I don’t regard it as a grim task at all

He endorsed George W. Bush in 2004, and later Tony Blair in 2005 because, for him, Iraq had “decided the matter.” He had already disavowed socialism and adopted libertarian leanings:

There is no longer a general socialist critique of capitalism—certainly not the sort of critique that proposes an alternative or a replacement

His consistently irrational defense of imperialism extended to apologia for America’s security regime’s war against whistleblowers and journalists. In 2010, when WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange published leaks that exposed war crimes committed by the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan, Hitchens found it appropriate to dishonestly smear him.

Christopher Hitchens’ is a curious journey: from a socialist to a full-fledged neo-conservative; from Ralph Nader to George Bush; from an anti-war activist to heralding the imperial agenda of “New Labour” and Co.

Norman Finkelstein’s comments on such “apostate” intellectuals are enlightening:

A rite of passage for apostates peculiar to U.S. political culture is bashing Noam Chomsky. It’s the political equivalent of a bar mitzvah, a ritual signaling that one has "grown up" – i.e., grown out of one’s "childish" past. It’s hard to pick up an article or book by ex-radicals – Gitlin’s Letters to a Young Activist, Paul Berman’s Terror and Liberalism… – that doesn’t include a hysterical attack on him. Behind this venom there’s also a transparent psychological factor at play. Chomsky mirrors their idealistic past as well as sordid present, an obstinate reminder that they once had principles but no longer do, that they sold out but he didn’t. Hating to be reminded, they keep trying to shatter the glass. He’s the demon from the past that, after recantation, no amount of incantation can exorcise.

On Hitchens, he further remarks:

Hitchens has now repackaged himself a full-fledged apostate. For maximum pyrotechnical effect, he knew that the "awakening" had to be as abrupt as it was extreme: if yesterday he counted himself a Trotskyist and Chomsky a comrade, better now to announce that he supports Bush and counts Paul Wolfowitz a comrade.

Ironically, a similar analysis of the sort of “abrupt” and “unpredictable” tendencies in media figures comes from Hitchens himself. In his 1980s essay “Blunt Instruments,” Hitchens presents an extraordinarily prescient critique of what seems to be his own future self:

In the charmed circle of neoliberal and neoconservative journalism, however, “unpredictability” is the special emblem and certificate of self-congratulation. To be able to bray that “as a liberal, I say bomb the shit out of them,” is to have achieved that eye-catching, versatile marketability that is so beloved of editors and talk-show hosts. As a lifelong socialist, I say don’t let’s bomb the shit out of them. See what I mean? It lacks the sex appeal, somehow. Predictable as hell.

Not inaccurately, in their 2005 debate, former British MP George Galloway described Hitchens’ turn as “the first-ever metamorphosis from a butterfly back into a slug.”

Till the day he died of cancer in December 2011, Hitchens refused to denounce his support for the “War on Terror.” In fact, just three months before he passed, he wrote a piece arguing for the necessity of “endless war” in the middle east:

We do have certain permanent enemies—the totalitarian state; the nihilist/terrorist cell—with which “peace” is neither possible nor desirable. Acknowledging this, and preparing for it, might give us some advantages in a war that seems destined to last as long as civilization is willing to defend itself.

Indeed, militaristic rhetoric of the sort above is indistinguishable from a standard David Frum speech. But, disappointingly enough, that is the hill Hitchens chose to die on.